Av: Konstanze Schmitt

2017-02-08

Notes for a Performative Research on the Workers’ Theatre

Workers’ theatre emerged in the 19th century in amateur theatre groups and workers’ clubs. It went on to be ideologized, formalized and broadly organized at the beginning of the twentieth century through its contact with the avant-garde. In the Soviet Union the Constructivists developed discussion pieces, and Proletkult (proletarian culture) emerged as a mass movement. Agitprop groups performed throughout the Weimar Republic for the workers’ cause. In particular, the methods of self-empowerment that were central to workers’ theatre stand in contrast to contemporary forms of theatre, which are shaped by the continuous search for (self-) expression. In the following I would like to present a few examples of this diverse tradition, in particular the beginnings of the agitprop and workers’ theatres of 1920s Germany. The text can be seen as an extension of a series of notes I created for Stephan Dillemuth’s project at Konsthall C earlier this year. Similarly to his project I hope this text will show the various relations workers’ theatre had to other art forms, particularly evident in 1920s Germany. But ttoday as well there are artists and theatre makers trying to reflect or update this by referring to the practice of the workers’ theatre.

1. Workers’ clubs

Let’s set the scene: in 1860s Germany, several educational clubs for workers emerged, some calling themselves “co-operatives for the acquisition and increase of intellectual capital”. It was the hope of various leaders of the workers’ movement that once workers educated themselves, the capitalists would no longer dare to offer them such exploitative wages. The workers’ theatre eschewed upper-class amateur theatre and its audiences, and instead shifted the emphasis entirely to the lower classes of society.

However, in the beginning this effort wasn’t consciously pursued, but developed organically as a mode in which to translate and communicate. For example when the first volume of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital was published in 1867, J.B.v. Schweitzer studied it thoroughly and published the results in the newspaper “Social-Demokrat”. In order to make the text’s difficult parts more accessible, he rewrote Marx’s theory into a dialogue between two people. The dialogue was not intended for the stage or live performance, but soon began to be performed here and there as a play in German workers’ clubs and soon Schweitzer published a version adapted for the stage: Ein Schlingel. Eine nationalökonomisch-soziale Humoreske in einem Akt. Perhaps more workers and functionaries were introduced to Marx’s ideas through these performances than through the book itself. At first Das Kapital sold badly, in 1867, a year after it was published, it had only sold 100 copies, although by 1871, most of the first edition had been sold. By that time, Ein Schlingel had been performed at least 15 times, and consequently about 1500 to 3000 people had learnt about the important theories of Das Kapital for the first time through the performance.

Imagine a scene: two workers after their shift, meet in a club. There they perform Das Kapital’s chapter “The Working Day” finding ways to openly explain how the working day is comprised of necessary and surplus labour, They discuss the instrumentalisation of their own bodies in the process of value creation, and of the struggle in their own interests, of law, force and class struggle. Everyone in the club, the performers and the audience, come to understand collectively what is at stake.

Moving on; in Germany in the 1880’s, socialism was banned through by state anti socialist law and political groups had to reform themselves. These law changes led to a great deal of cover-up activities. One example of cover up activity was the formation of clubs that advertised themselves as promoting culture and sports. Here workers could meet informally and develop forms of collectivity, free of the demands of party politics hence liberated from political or cultural top-down agendas. The workers could also organis events such as “Bunte Abend” (colourful evenings) similar to a variety show where all participants contributed with their specific interest or skills, giving space for all sorts of performances. The evenings consisted of singing, dancing, acting, tableaux vivants1, recitals, proclamations. Between 1880 and 1900 this type of participatory theatre “by workers for workers” had grown popular among the working class and was an important tool for self-education. However, at this point, the state authorities began to regard these performances as a form of highly dangerous agitation and therefore censored them. Yet, the soon-to-be official socialist parties also prohibited them, as they considered the activity as a waste of time, advising the participants to rather engage in straightforward political work and/or the reading of the German “classics” — thereby promoting a bourgeois and canonized idea of culture.

From 1890 onwards, the movement of the German system of “Volksbühne” (People’s Theatre) became a competitor to the self-made theatres of the workers. In Volksbühne, it was more “professional” writers and actors that were illustrating workers’ topics. Originally intended to attract an audience of workers, their aim was rather to entertain a new class of low-wage white collar workers with more-or-less populist and socially oriented productions. Instead of making an independent theatre, with the idea of entertaining and educating themselves and others (“education and agitation”), the workers were to be attracted by entertainment alone in the framework of bourgeois sentiment. Nonetheless, smaller groups maintained the earlier, more left-wing approaches of the first workers’ clubs. They became important models for the development of the “agitprop troupes” in the 1920s. One of the first “professional agitation troupes” was Boreslav Strzelewicz’s “Gesellschaft Vorwärts”, a group of three people who toured different workers’ clubs, theatres and festivals. Their programme included songs and poetry recitals, but also short farces and comedies. The group could react quickly to local events in the places they visited, and incorporate current political developments immediately into their programme. In order to address their audience more directly, names and locations were left open in their scripts. Their songs, poems and farces were not primarily instructive and informative but tended rather to be emotional and full of pathos; nevertheless, their idea of a revue with a variety of different acts provided an entertaining structure for propagating socialist issues. Such a “Nummernprogramm” (or varied programme) could free itself from the “unity of action, time, and place” demanded by classical theatre. News and other printed matter of political relevance just needed to be put into the form of a dialogue or worked into a montage. Thus the troupe paved the way to the political revue and agitprop which developed in the years following the First World War.

2. Party and Protagonism

Agitprop (agitation and propaganda) emerged in the Soviet Union after the Bolsheviks took power in 1917 as a way to politically agitate the masses and to convey the new political and social form of communism. At the forefront was the call to contribute to the construction of the new society. For the agitprop troupes it was about flexible, rapid, on-site deployment; productions were made with little to no scenery or stage, and costumes were replaced by overalls or similar uniform work-wear. The mostly short pieces alternated between the various scenes of the piece and a speaking choir. Songs were also always used; while the audience was being presented with recognizable situations during the scenes, the choir would commentate and appeal to the workers as a class. The pieces were adapted to current political realities and locations with the intention of criticizing, propagating and agitating.

Caption: On March 28, 2010, domestic workers demonstrated in downtown Madrid for labor rights and rights of residence. The women of Territorio Doméstico, a platform of organized domestic workers, individuals, and activists, wheeled this collectively painted wagon through the streets. It was a stage set for several scenes of an agitprop performance within the frame of the demonstration in which domestic workers give an account of oppression and resistance in their daily lives.

Konstanze Schmitt, Territorio Doméstico, Stephan Dillemuth: Triumph of the Domestic Workers (2010). Performance in public space, video, installation.

While in the Soviet Union agitation and propaganda were important political tools from the start, and the

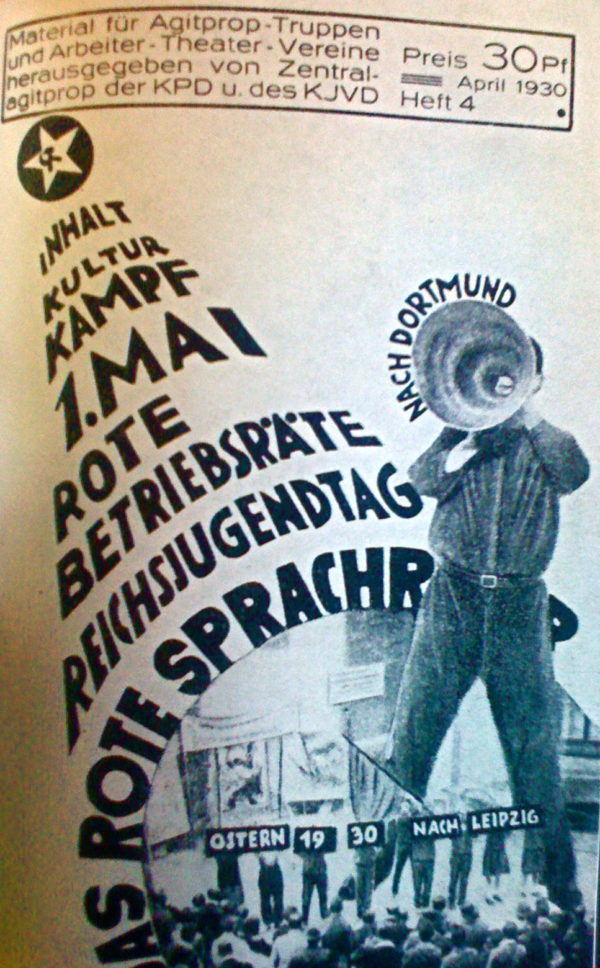

avant-garde took advantage of the “organizing function of art” (Sergei Tretyakov), it took the Communist Party of Germany (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands) until the mid-1920s to discover that culture and art were important in the struggle for hegemony of the state. A tour by the famous “Blue Blouse” agitprop troupe from Moscow in 1927 sparked an agitprop theatre boom in the Weimar Republic. In 1929, there were about 300 agitprop troupes in Germany. The “Rote Sprachrohr” troupe from Berlin was one of the most influential groups; it was also the mouthpiece (Sprachrohr) of the German Communist Party. The mass organization of workers in education, sports and music clubs, which had existed since the 1860s (and which, especially at the time of the Anti-Socialist Laws, were popular political meeting places), was empowered and politicized through those associations: in 1928 about half a million workers were organized in the Arbeitersängerbund (Workers’ Singers’ Union) in Germany. That is around ten times more than in in 1908; moreover, the movement was no longer dominated by men, as many women had joined the formerly all-male choirs. The communist sports and leisure movement is portrayed in the film “Kuhle Wampe”, 1932, directed by Slatan Dudow and written by Bertolt Brecht.

The Rote Sprachrohr also wrote about their practice, e.g. in “How to build a scene?”, published in 1929 in the newspaper Rote Fahne (Red Flag), they described their approach, the main characteristics of which are:

1. Agitprop is not a spectacle because the performer (“worker player”) expresses her/his own opinions.

2. Making artistic propaganda means: collective writing, i.e. each member of the group participates in the collection of material (mainly from the latest news stories and everyday observations) and in the writing of the text.

3. It is good to use rhymes and songs in the text as these can be memorized more easily. If the group works quickly and efficiently, current events are sometimes communicated even “faster across the stage than they are in the press.”

4. All performers have the task, besides working on texts and scenes, to educate themselves politically.

The Rote Sprachrohr circulated its plays and songs under what today would be referred to as a Creative Commons licence. To make their texts and their practice accessible to as many people as possible the group published the magazine Das Rote Sprachrohr, in which they also gave advice on how to produce their plays: “We have intentionally not provided precise performance instructions for individual scenes. The type and form of the performance must be based on the troupe’s joint discussions during rehearsal. The short directorial remarks should not be viewed dogmatically, but rather as proposals or suggestions for your own, intensive process of working through the material. We want no schematics, no rigidity, we want liveliness. The measure can only be the level of training of the respective group. Scenes that have been written in Berlin dialect must be transferred into a local dialect. Likewise, it is necessary to extend the storyline by using theatrical approaches to local events. It is good to put banners on stage with slogans taken from corresponding scenes.”2

In 1932, Rote Sprachrohr had more than 50 members and 4 brigades: children’s, touring, active and reserve (the latter for courses and new productions).

In “So oder so?” (“Like this or like that?”) the basic principle of Forum Theatre by Augusto Boal has already been created. Forum Theatre is a form of agitation theatre and is the central method of the Theatre of the Oppressed. Augusto Boal developed it in the 1950s and 1960s in Brazil. Unlike agitprop theatre, Forum Theatre often takes place with groups who know each other because they work, study or live together. Through conversations the group develops a scene around a particular problem. This is often performed by actors and uses all available theatrical means; characters are often stereotyped (the entrepreneur, the landlord, etc.). At the end of the scene, the performers ask the audience whether they agree with the depicted reality or with the solution to the problem. Those who do not agree take on the roles that they want to change, the others continue as before. The original cast remain in an advisory capacity on stage. One of them takes on the directorial role, explains, moderates, makes sure something is happening. It should become clear to people that it is up to them to change the reality and that it is not simple, but also not impossible. Discussions take place at intervals throughout and at the end.

Agitprop theatre is somewhat more authoritarian; the audience remains in its role. Nevertheless, the chosen

form — playing a scene twice with different outcomes — makes the same statement as a scene in Forum Theatre: reality can be changed. (And the private is political.)

3. Collaborations

The development of the Epic Theatre – the not illusionary, not dramatic theatre – in Germany can be traced from the early proletarian festivals and the “Bunte Abende” of the “workers’ self-help” through to the variety-programming of the “Gesellschaft Vorwärts” and chorus chants, right up to the more widely known theatre of the 1920s: the agitprop troupes and Political Revues, as well as the revolutionaries of the bourgeois theatre and music, Erwin Piscator, Bertolt Brecht, and Hanns Eisler, who developed new forms of theatre in collaboration with the workers’ movement.

Hanns Eisler for example developed songs for Rote Sprachrohr, as well as theory and pieces of music for the workers’ singers’ movement (Arbeitersängerbewegung). For Eisler the “Neue Musik” was a coherent tool in the struggle of a new movement: ”The revolutionary sections of the working class always took a progressive attitude towards musical matters because the workers knew very well that the struggle of the working class, led by new ways of thinking and organizing, is also in need of a new style of music.”3

It is in this sense that Brecht further developed the Epic Theatre: in order to achieve the active participation of workers in the realization of art/theatre and in political discussions, he produced, together with the composers Paul Dessau, Hanns Eisler and Kurt Weill, the avant-garde concept of Lehrstücke.

In 1930, Brecht and Eisler created the Lehrstück “Die Maßnahme” (“The Measures Taken”). It was the first great work made in collaboration with the workers’ singers’ movement. For the premiere three Berlin workers’ choirs rehearsed the piece (for the most part untrained singers without knowledge of musical notation). Fittingly, the rehearsals took place in the evening, the premiere beginning only at 11.30 p.m. Hanns Eisler wanted “to write a piece for those it is intended for, and for those who can make use of it: for workers’ choirs, amateur theatre groups and student orchestras, so for those who neither pay for art, nor get paid by art, but rather those who want to make art”. This definition corresponds with one of the definitions of the Lehrstück: That above all it is those on stage, developing and discussing the piece, who learn. Like all forms of workers’ theatre, the Lehrstück is about the dissolution of the boundary between producers and consumers, towards a form of art in which all participants are active.

“Die Maßnahme” was banned because of its “incitement to class struggle”; the Communist Party on the other hand found it too idealistic. At the time, the realism debate was in full swing, the experimental art forms and ambiguous “queer” forms of representation were dismissed. The doctrine of the Communist Party praised Stalin’s “socialist realism”, which suppressed the aesthetic (and political) experiments of the coming decades. The music, however, was praised by all sides.

In the workers’ theatre of the 1920s and 1930s there emerged a new image of humanity, one that was not only discursive, but one that was also characterized by industrialization and the rational(ized) approach to the body. In the Soviet Union, Vsevolod E. Meyerhold developed “Biomechanics” as a system of movement for actors. In New York, a dance scene emerged that was largely shaped by migrant women. Both movements are fundamental to our current understanding of the body on stage.

4. A New Learning Play

There has been several contemporary attempts to re-use workers theatre methods. Two examples:

In Stephan Dillemuths work at Konsthall C in Stockholm, workers theatre techniques were re-implied and performed by a group of 16 members who rehearsed, re-performed and discussed their working conditions throughout the making of the project. Workers theatre in Sweden has a different history: It began in 19th century as folk theatre festivals in the countryside, where the factories were. Workers performed in the forests on stages with scenes made of bushes which later led to the development of slapstick or “Buskis” Theatre. Stephan Dillemuth’s final installation consisted of a stage with a built forest. The trunks and branches of the trees consisted of plaster casted body parts the theatre member’s use when they work, forming some sort of ”human-forest machine”, yet the political subtext to Dillemuth’s work also appeared when standing and looking at forest from a particular point in the gallery, as the trees, branches and limbs of the workers merged together and formed the word ‘STRIKE’.

Also the Russian collective Chto Delat has updated and re-implemented the idea of Brecht’s Lehrstücke in recent years with their Learning Plays (Lehrstücke), that have taken place in various (mostly art) contexts and with changing participants. In the introduction to their learning play: Where has Communism gone? (2013), they write:

“The ghost of communism still wanders around, and to transform it into a commodity form seems a good way to finally get rid of it. Conferences and artistic events dedicated to the idea of communism are going on one after another, speakers are paid or non-paid, advertisement production machines function well, and the sphere turns round as before. But beyond this exhausting machinery of actualization and commodification, we still have as a potentiality this totally new desire of communism, the desire which cannot but be shared, since it keeps in itself a “common” of communism, a claim for togetherness, so ambiguous and problematic among the human species. This claim cannot be privatized, calculated, and capitalized since it exists not inside individuals, but between them, between us, and can be experienced in our attempts to construct this space between, to expose ourselves inside this “common” and to teach ourselves to produce it out of what we have as social beings.”4

In the attempt to update workers’ theatre, it is clear that its form and content are inseparable. Walter Benjamin’s call for the necessary connection between tendency and quality5 is proved — in the amateur theatre of the workers’ clubs in the nineteenth century, in the revues and agitprop performances of the Weimar Republic, in the Lehrstücke, but also with those who, like Chto Delat and Stephan Dillemuth, pick these methods up and take them further. It is not simply a call for something common: the class, the spirit of communism, the emancipation of people. Aesthetics too are concerned with this issue — the question of producing something in common, a ”commonism”6 among all participants.

Konstanze Schmitt is an artist and theatre director. She lives and works in Berlin.

FOTNOTER:

1. Tableaux vivants which means ”living pictures” is a form of theatre in which participants depict an image through a freeze-frame method whilst a narrator describes the presented situation.

2. Published in: Rote Fahne, 1929. Quoted after Hoffmann/Pfützner: Theater der Kollektive. Proletarisch-revolutionäres Berufstheater in Deutschland 1928-1933. Stücke, Dokumente, Studien. Berlin 1980.

3. Hanns Eisler, Werke, Leipzig 1982, p. 257

4. http://chtodelat.org/category/b9-theater-and-performances/where-has-communism-gone/

5. See Walter Benjamin, The Author as Producer (1934)

6. Political scientist and economist Friederike Habermann developed this term to describe a society based on common-based peer production.